The tale behind Bob Dylan’s “Time Out of Mind” spins a narrative tinged with myth and marketing: A grief-stricken Dylan, mourning Jerry Garcia’s passing and sensing his own mortality creeping closer, delved into his beloved blues records to confront the encroaching dread. He shared his resulting lyrics with producer Daniel Lanois, who was struck by their haunting potency. Thus began a journey into the studio to craft an album that felt like a séance and a final testament rolled into one.

Yet, as with many stories surrounding Dylan’s albums, this one blends elements of legend and promotional narrative. The Bootleg Series often either challenges conventional wisdom or amplifies myths. “Fragments” might be the first release that accomplishes both. Amidst the overwhelming nature of the Bootleg Series or its seemingly exclusive appeal to devoted Dylan aficionados, “Fragments” offers a clear narrative arc: Disc One presents the final studio album, freshly remixed to reacquaint listeners with its enigmatic shadows and immerse them in its evocative atmosphere. The subsequent four discs—two featuring unreleased outtakes, one previously available, and a live set—reposition “Time Out of Mind” as a rebirth rather than a swan song.

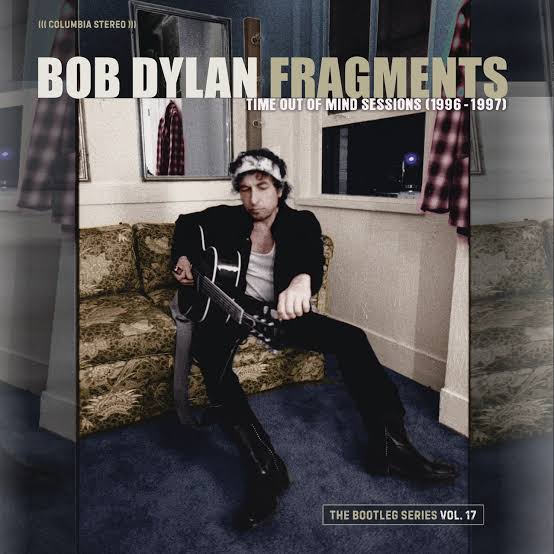

What becomes evident over the course of the six-hour set is that “Time Out of Mind” is, above all, a story of mood—a singular pursuit by an ensemble. The album’s creation was protracted, painful, and vividly alive, with its somber demeanor largely a product of theatricality and shadow. Dylan, ever the chameleon, assumed a persona, donning a black jacket and inhabiting a character for fresh perspectives. Lanois intensified the gloom, enveloping the album in a damp chill of effects pedals and reverb until Dylan’s voice seemed to emanate from the beyond. However, as the new mix on “Fragments” emphasizes, his morose façade was akin to stage makeup, and the brooding atmosphere, mere theatrics.

The narrative commenced fittingly in an old, picturesque playhouse dubbed the Teatro by Lanois, replete with storybook embellishments—cobwebbed 16mm projectors, dusty mirror balls. Dylan and Lanois embarked on looping jams inspired by Charley Patton’s old 78s, laying the groundwork for the tracks with bassist Tony Garnier and drummer Tony Mangurian. The resulting formidable sound startled everyone present; sound engineer Mark Howard recalled the hair on his arms standing on end.

However, Dylan found it difficult to work so close to home and family, which now included six children and multiple grandchildren. The sessions shifted to Criteria Studio in Miami, a storied space with a rich musical history. Lanois, unfazed, transported his invaluable tube microphones and decaying tape loops to this concrete box. Nevertheless, this relocation marked the onset of a schism between the two visionaries—a schism that would define and nearly overwhelm the sessions. The two obstinate individuals seemed destined for perpetual discord. Lanois rarely communicated with Dylan before or after takes, and entire days passed in frigid, uncomfortable silence.

Meanwhile, Dylan appeared intent on complicating matters further. He purportedly felt haunted by Buddy Holly and, as a tribute, assembled his own spectral rendition of the Crickets, drawing from his touring lineup, session royalty, and beyond. Ultimately, at least a dozen musicians found themselves crowded into Criteria, with Dylan as their enigmatic maestro. Dylan experimented with songs in different keys, abruptly changing mid-performance and expecting the band to adapt instantaneously. Playback sessions were chaotic, with musicians audibly colliding as they struggled to adjust. Recognizing the limited opportunities to capture each song before Dylan grew bored and moved on, Lanois instructed musicians to refrain from playing if they couldn’t navigate the changes.

Nevertheless, amidst the studio turmoil, the musicians achieved a loose, sprawling cohesion. Guitar lines teetered on the brink of dissonance with the drums, only to synchronize seamlessly. These were not driving rock anthems; yet, there were three or four drum kits thundering away at any given moment. The music surged forward like a massive, dark thundercloud, with guitar echoes melding into a cacophony of drums.

The unreleased outtakes on “Fragments” unveil some of the extraordinary moments scattered throughout the journey. On Disc 2, Dylan’s rendition of the folk standard “The Water Is Wide” exudes a rare devotion, with Garnier and Mangurian providing subtle, understated accompaniment. On Disc 5, the original take of “Can’t Wait” captivates with its ominous atmosphere, highlighted by Dylan’s block piano chords and Lanois’s impressive riffing. The song’s mesmerizing darkness is palpable, with Dylan infusing the lyrics with the unhinged fervor of a Shakespearean actor unleashed in a Hollywood blockbuster.

The additional discs offer the customary delights of the Bootleg Series: an alternate version of “Cold Irons Bound” featuring striking alternate lyrics, and live renditions of “’Til I Fell in Love With You” and “Standing in the Doorway” imbued with hints of roadhouse blues, soul, and gospel. However, the true allure of these recordings lies in witnessing session legends like Mangurian, Jim Dickinson, and Bucky Baxter—whose contributions were the lifeblood of American music—displaying moments of vulnerability, reverence, and uncertainty. Years later, they still spoke of these sessions with a mixture of trepidation and admiration.

This lingering unease underscores what sets “Time Out of Mind” apart in Dylan’s discography, perhaps even making it unique: it was a product