In 1971, radio luminary John Peel introduced a 24-year-old musician during a broadcast of Pick of the Pops as “a young man who writes good songs and makes good records, but never seems to get the recognition he deserves.” At that point, the artist known as David Robert Jones wasn’t on a trajectory toward stardom. Starting with the saxophone at age 13, he navigated through various small bands in high school, first adopting the moniker Davy Jones, and then changing it to David Bowie to avoid confusion with the Monkees singer. In 1967, he released a self-titled album of music-hall-style rock on a small label, but disagreements over singles led to a partnership collapse. Following this, he took diverse paths including a stint at a Buddhist monastery in Scotland, involvement in a mime troupe, and forays into experimental performance art. Eventually, Bowie landed at Mercury Records through fortunate connections, remaining relatively under the radar until his cosmic single “Space Oddity” briefly catapulted him into mainstream consciousness five days before the Apollo 11 launch in 1969. However, his third album, the eclectic and single-less The Man Who Sold the World, found its success largely localized to Beckenham, England.

Talented yet creatively disordered, Bowie found himself at a pivotal juncture. “In the early ’70s, it really started to all come together for me as to what it was that I liked doing,” he reflected in 2014. “What I enjoyed was being able to hybridize different kinds of music…. I didn’t really see the point in trying to be that purist about it.” This renewed perspective, coupled with a transformative journey to the United States in 1971 where he mingled with creative luminaries like Andy Warhol and Lou Reed, rendered Bowie “more cynical” about the confines of artistic boundaries and more innovative about his role within them. Returning home to England, back to his newborn son and a piano gifted by a neighbor, the burgeoning artist pieced together what would become his fourth record, the first he ever co-produced and his initial effort after signing with RCA: Hunky Dory. This album marked a turning point for Bowie. As he put it, it was “the album where I said ‘Yes, I understand what I’ve got to do now.’”

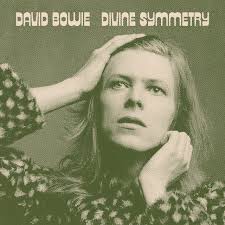

Divine Symmetry, subtitled An Alternative Journey Through Hunky Dory, emerges as the latest box set delving into Bowie’s musical repertoire. The 4xCD collection explores the year leading up to the album’s release, featuring previously unreleased tracks, demos, live recordings, and studio sessions from the era, along with updated mixes. Accompanying the music is a 100-page book containing primary documents, insights from insiders like co-producer Ken Scott, and liner notes by Tris Penna. Additionally, there’s a separate booklet featuring Bowie’s handwritten notes, offering an intimate glimpse into his creative process through scribbled footnotes, discarded chords, and fashion sketches. This compilation provides a window into Bowie’s mind during the most pivotal transition of his career, offering retrospective insights into his persona formation. While Divine Symmetry isn’t the first attempt at documenting Bowie’s artistic evolution, it feels particularly personal, perhaps due to its smaller scale (unlike the massive 12-disc Five Years set) and the volatility of this period in his life. The stakes feel higher: listeners yearn to witness his journey toward the success we now know exists. Within this collection, we hear Bowie beginning to shape the theatricality of Hunky Dory: practicing, experimenting with lyrics, exploring different arrangements, making mistakes, and engaging in playful banter. Simultaneously, he’s also laying the groundwork for his next record, a project called The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars.

Divine Symmetry’s demos and offcuts peel away the warm, piano-centered veneer that characterizes Hunky Dory, revealing a rawness that suggests Bowie’s music was always otherworldly. On subsequent albums like Ziggy Stardust, Bowie would refine the interstellar, guitar-driven sound of “Space Oddity” and The Man Who Sold the World, deriving a mature glamor from Hunky Dory’s grounded orchestration. The piano served as a rich yet mellow palette, enabling Bowie to experiment with a flexible and distinctive yet timeless instrument. Tracks like the forgotten “How Lucky You Are (aka Miss Peculiar)” offer early glimpses of Bowie’s keyboard work, with rudimentary melodies and buoyant rhythms in a waltz-like structure. A burgeoning vaudevillian spirit emerges, hinting at what would later become more fully realized on songs like “Fill Your Heart” (originally a Biff Rose tune eventually recorded by Rick Wakeman on a Bechstein grand piano). Similarly, the “Life on Mars?” demo, a brief piano sketch, provides a glimpse into the cinematic masterpiece that would follow. Before delving into “a God-awful small affair” in crystal-blue eyeshadow and auburn hair, Bowie was simply a man at a piano, softly singing about a “simple but small affair.” His growth as a lyricist is evident in the melodrama of his lines.

The live recordings offer a unique perspective, revealing which of Bowie’s instinctual choices he ultimately retained. In the John Peel version of “Kooks,” accompanied by gentle guitar strums beneath his voice, Bowie delivers a lullaby-like rendition compared to the more oom-pah-driven studio version. Despite being recorded for broadcast, it feels as though Bowie is serenading his son directly, adding a tender dimension to the song’s familial theme. The “Queen Bitch” demo and live recordings are notably mellower and melodious compared to the acrobatic talk-singing of the final version, where verses exude an intensity already present in the chorus. While his performance on Peel’s show sounds restrained, Bowie’s liberated rendition of “In her frock coat and bipperty-bopperty hat!” offers insight into the song’s intended character. As the jealous narrator observes a male lover courting a sex worker outside his window, Bowie’s evolving exploration of sexuality and identity becomes more heartfelt and less campy. The box set also features early versions of songs that were ultimately sidelined, such as the folky, harmony-laden “Tired of My Life (Demo)” and the previously unreleased “King of the City (Demo).” These tracks highlight Bowie’s evolution as a lyricist, even within the album’s creation period. Lines like “Come back to the real thing, baby/I’ll make it all slow down, baby/We’ll tell our friends we’re finding our own way” pale in comparison to the mind-bending imagery of “watching the ripples change their size.” The inclusion of “Bombers,” a song Bowie described as “kind of a skit on Neil Young,” emphasizes his evolving satirical approach to societal norms. Initially left off the original Hunky Dory at the last minute